Last time, I told you about how when I was 11, my dad suggested I write to the letters page of our local paper as way to ‘get started as a writer’. Nice idea from my dad, poorly executed by me. This newsletter is a companion to that one, so if you didn’t catch it, or want a recap, click below.

So. About a week or two ago, back in the early stages of writing Dear Village Print, I realised I had something I could share at the end of that newsletter which would wrap things up pretty nicely. But the more I worked on the newsletter as a whole, the more I found there was to say about the other stuff. You know, the whole thing about those old letters showing my writing process, the inner critic, my quest for sincerity, getting published in Just Seventeen, all of that.

And I thought, if I go ahead and add this last thing, this newsletter is going to be too long.

And I didn’t want that last thing to be glossed over or rushed, because it means something to me.

So I decided to write about it in a separate newsletter, the one you are reading now, and I must admit now that I’m here I’m finding it hard to say this next bit; however I phrase it sounds abrupt or not quite right, so I’ll just have to say it.

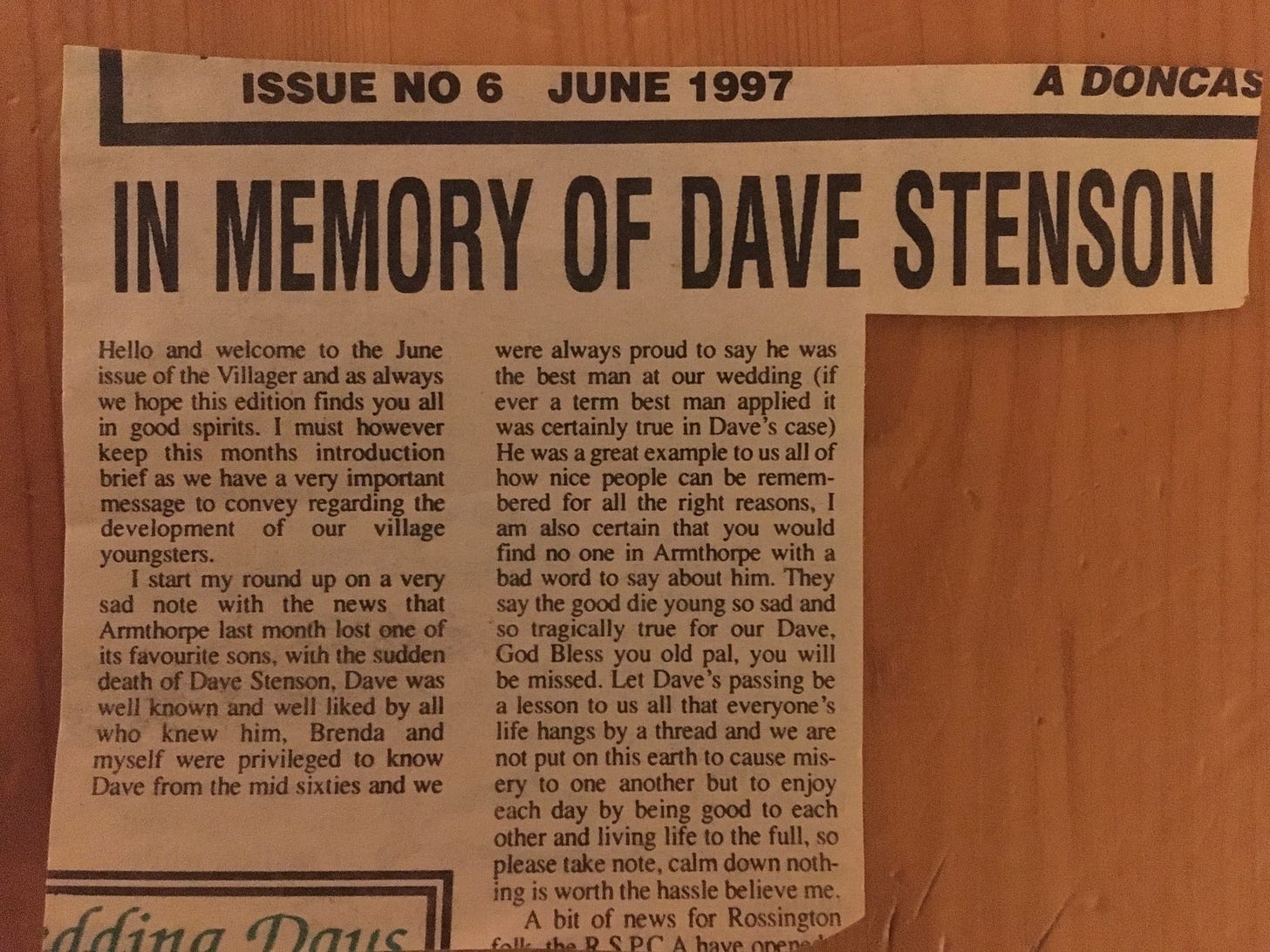

Five years after my dad encouraged me to write to The Village Print, he died, and The Village Print wrote about my dad.

Here’s the cutting from their front page. I really wish I’d kept the whole paper, or even just the complete front page, but this was the important part at the time.

Looking at this now, 26 years later, is an interesting experience, and I’d like to share a few things that have come to mind in the last week as I’ve been writing and thinking about this.

Before anything else I want to say that as lovely as this tribute is, it does that thing we do when people who we hold dear have just gone: we speak of them as flawless. And I know why we do it, and it’s exactly what is appropriate to do here on the front cover of a paper going into however many houses and businesses, and I wouldn’t expect anything else. This is how the editor wanted to express how he felt about his good friend, Dave, and it’s how he felt he could honour him.

And that leads into something else I’ve been thinking about: how whatever words we choose when we write about someone, whether they are still with us or not, we can’t ever give the whole, fullest picture, because, of course, people are big and contradictory and complex.

And also — what we think, remember or feel is always in flux, depending on where we are ourselves in that moment.

So.

I wanted to say that, because whatever I go on to say next about my dad, as much as I will try to give a full-ish picture (and therefore not flawless) I can only give it to you through my lens, and what I think, remember and feel now.

And if you’re thinking WHERE’S THE DIARY STUFF, TERESA? I promise that this all magically, unexpectedly, threads together by the end.

What really strikes me the most about the Village Print tribute is the sense that my dad ‘belonged’ to the place where he grew up. I like how he’s called a favourite son of the village, and a village youngster. This makes total sense to me, because despite being quite well-travelled, my dad was also really rooted to Armthorpe. He always seemed like the very definition of a big fish in a small pond to me. I knew he was popular and well-liked, just as the editor of the paper gets across.

My parents didn’t get together until my mum was 30 and my dad was almost 40 — and they were divorced before I even exited the womb a year or so later (honestly). But my mum told me that when she was a teenager my dad was seen as a local heart throb, because he looked a bit like Elvis, and he had a really glamorous girlfriend. I have a black and white photo taken in the 1960s of my dad and this lady on a beach in the south of France, and can confirm that she is glamorous, and I’d say my Dad is a bit Elvis-y, but he looks more like a cool beat poet. I think.

It was actually the glamorous girlfriend who gave me the photograph after my dad had died. She was back in town from America (where she’d emigrated to) and was organising the sale of her childhood home, on the street where I lived. She’d happened upon the photo and thought I should have it. She was kind, and she looked wistful as she said nice things about my dad. I didn’t tell her that he, on the other hand, had never had anything nice to say about her. Things between them had ended badly and my dad was great at holding a grudge.

Further evidence of my father’s grudge-holding capacities: so intense was his dislike / hurt / who-knows-how-he-really-felt for my mother, that he didn’t speak to her again after they broke up. Not once. Not even to discuss me, cooking there in the womb. And it wasn’t like they’d just had a fling, they were married and lived together until that point.

After I was born, I was transported to and from my dad’s by his sister every Saturday and Sunday for visits. This went on for a few years, until I was three or four, then we had a break in contact until I was ten. Too much to go into here, but nothing awful. As such, I was never in the same room as both of my parents at the same time. Not ever.

My dad was confident, and a great conversationalist. He knew a lot about history, and he had a brilliant singing voice. And yes, he did look a bit like Elvis when he was younger, and he also ended up going on a similar physical trajectory as he got older. He ate too much saturated fat, liked a drink, liked a smoke.

He went to a Grammar school, and spent most of his adult life working in a glass factory, with a stint living in Newquay, and travelling to France, Canada, America. He liked to wind me up, all the better if it gave him a funny story to tell other people. But I’ll say he did it with affection. He could be judgemental. He was stubborn. He was witty.

He wanted me to do well academically first and foremost yet supported all of my artistic endeavours. He didn’t have a lot of money but he sourced expensive acrylic paints and an easel when I was twelve and had said I wanted to be an artist, and a guitar plus lessons when I was fourteen and wanted to be in a Britpop band. And of course, he suggested I write to the local paper because I wanted to be writer.

I was 16 when he died. In fact, the last time I saw him was my 16th birthday; he had a heart attack a few days later. I’ve always felt lucky that the last time we saw each other was a good, happy occasion. Not because it was my birthday, but because there was a lightness between us that wasn’t always there.

We didn’t have a lot in common, and because I only really got to know him when I was ten (I have very few memories of the early years of visiting him, but of course he remembered it all with clarity, something that annoyed me) there was a distance between us. I deliberately kept him at a distance, I can see that.

But that day, my 16th birthday, I dropped round to see him after school and we had a great conversation because we found some unexpected common ground. I was really into the 60s / 70s music and fashion revival that was part of indie culture at the time, and I told him I wanted to get my provisional licence and (somehow) get a Vespa or a Lambretta (didn’t ever happen) and Dad told me something that I just thought was so very cool: he’d been an original mod in the sixties, and he’d had a Vespa.

My dad, who by this point was 56 with a comb-over and a pot belly and who mostly listened to uncool (to me) rock and roll or country music, had been a mod who rode a Vespa?! (Remember, at this point I hadn’t seen the beat-poet-on-a-beach photo)

And he rode his Vespa to the hospital to come and see me just after I was born!

(I was in the nursery bit where all the new babies are, not on the ward with my mother, obviously, or he might have had to look at her.)

I remember we were both energised by this bonding moment, and then he went upstairs to get something for me: an old shirt of his from the 60s, paisley, but not garish, in mint and cream. I loved it. I’ve got an awful feeling that I don’t have that shirt anymore. But I wore it for a few years after he died, and I wore it with wooden beads and corduroy flared trousers, because I was very cool.

I’ve always felt lucky that we had a good day that last day, and I’ve always wondered what it would have been like to know him as I got older. I wonder if we’d have been able to find more common ground, and if I’d have been able to let the distance between us shorten.

Time for the diary share.

When I was 12 Dad took me on a week-long trip to London. It must have cost him a fortune; I think he’d had a pay-out for something or another. His aim: to inspire me with culture and history. He made it into a whole week of museum visits, hitting all the big landmarks, and doing touristy stuff blended with educational stuff. He definitely wanted to widen my world view, and get me interested in what I guess were his interests, mostly history.

I, on the other hand, didn’t care about the past; I had an eye on my future. Something transformative happened on day two of that trip: we went to the Palladium to see Joseph and The Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat, and a fire was lit within me.

Honestly, I loved that musical with my whole heart.

(Honestly, I still do.)

If you’re wondering what’s up with the paper and those … gnomes? who are clearly laughing at my very important life decision — it’s a notebook that I think my Grandma gave to me, the idea being I’d take it to London to keep a record of the things we did each day.

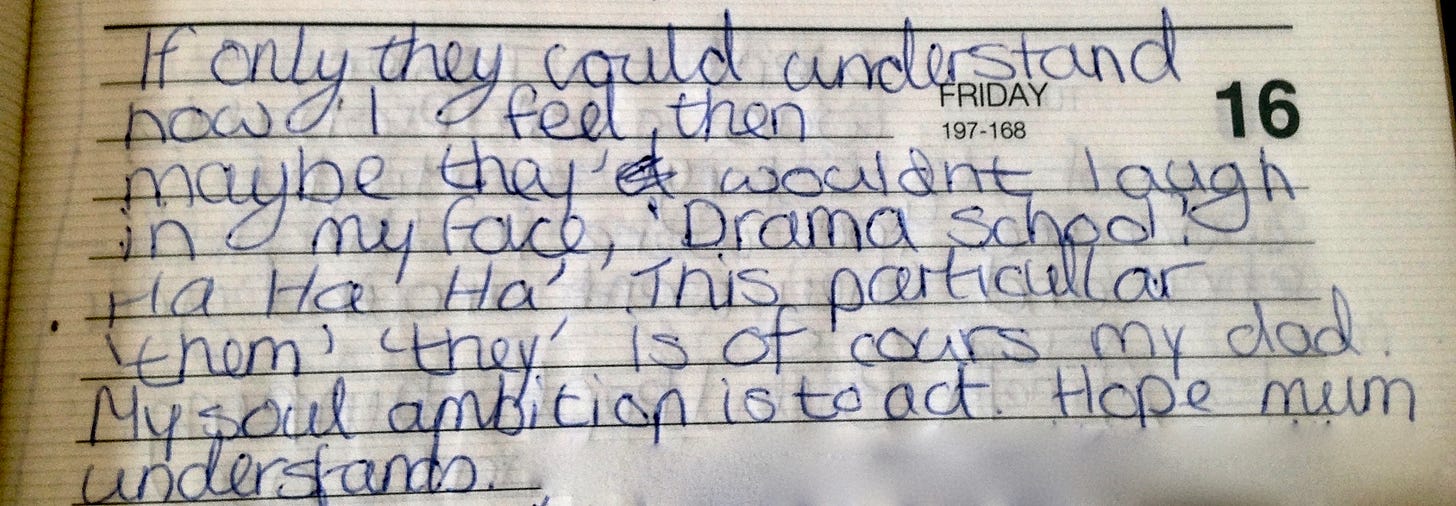

But then there’s this below, written in the diary I kept at home. Did I fill this in when I got back, retrospectively? Maybe.

Anyway, the point is, I am saying I want to go to drama school and I am doing a great job of being very dramatic about it.

“Soul ambition” — the most perfect spelling mistake.

It’s interesting to see there’s a contradiction here in what I said about my dad earlier: I said he was supportive of my artistic endeavours, yet here he is not really taking me seriously about wanting to be an actress. I think this ties to the other thing I said about him: he liked to tease me and wind me up.

Huh.

And I guess that goes back to how we can’t get the complexity of a person, or our memory of them, down in words. Maybe because words are solid while people, and our memories of them, are undefinable and always moving, even after the person has gone.

This newsletter is way longer than I intended.

I’ll end with two photos.

Here’s Dad, on the beach in the south of France, glamorous lady edited out, just because I don’t know her and all that.

And here’s me on our London trip. It’s 1993, I’m 12 years old, hair is freshly permed, and I’m wearing one of those hats like Blossom wore.

The reason I look a bit startled is because I’d just turned around to the camera after giving some change to a busker who was singing Everything I Own, by Bread. I didn’t know the song then, but I really liked it, and somehow, I could recall the chorus for years later, but not very accurately, not enough for anyone to know it if I tried to sing it to them, even my dad. And of course I had no way of looking it up back then.

At some point years later I heard it on TV or the radio (pre YouTube etc) — maybe it was the Boy George cover — and anyway I was pretty thrilled to finally know what this song was. I still like to listen to it here and there now.

Oh crap so that was going to be the last line/sentiment of this newsletter BUT I just Googled Everything I Own to make sure I was right about it being a Bread song originally — it is — and would you know it, it’s not a love song as most people think.

I’ve just discovered that the songwriter, David Gates, wrote it about his dad, who died when he was young.

Well. That’s pretty weird.

Putting together the pieces of weirdness: So I was listening to that song just as my dad took that photo, I went on to keep the song in my mind until one day I found out what it was, then I chose to include that particular photo here, which made me write about the memory of the busker and the song, here in this essay about my dad who died young, only to find out the song is about a father who died young.

I’m feeling like time just collapsed a little.

If you’re still here, thank you. This was a tricky one to write. I genuinely thought it’d be quite brief, but it became its own thing as it went on. That’s what I’m enjoying about this process of sharing my diaries with you, finding the connections as I go, sometimes joining dots, and sometimes being taken totally by surprise like I just was.

I think I’ll share something lighter next time, maybe a collection of the inside covers of my diaries where I warn people to not read on, and once where I used the space to work out how much I loved Tom Cruise using an elaborate mathematical system that involved counting the letters in our names, and must be legally binding.

Until next time,

Teresa x

PS: So many of you have been sharing this newsletter and posting on social media, and I am truly thankful for each share or mention or forward to a friend. I think it’s going to be the best way for the newsletter to grow, so please feel free to spread the word or send this to a friend or two.

And are we friends on Instagram? I share behind-the-scenes bits and bobs about my diaries and the writing of this newsletter in my stories there! Come say hi? You can leave comments there too, if you’re not able to comment on Substack.

And also, you are always free to hit reply here and email me back if you’d like to.

Also: went to see Joseph this Christmas.

Soo poignant Teresa. Love how you weave it all together. I'm doing that googling thing too and discovering weird sh*t. Only connect.